Are Green Buildings Biophilic? Why the answer matters, particularly in Asia

Article by Nirmal Kishnani - Vice Dean at School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore

Let’s start by unpacking the concepts.

‘Green’ in Asia is dominated by certification tools. There are now some 14 national variants – not unlike LEED in the US – each offering tiered ratings at the building scale, some at the urban scale. The rating is determined by an aggregated score, the result of compliance with requirements that focus on measurable outcomes such as energy and water efficiency.

‘Biophilic design’ has a more qualitative goal, specifically human well-being tied to the presence of natural elements in buildings, such as greenery and water, or access to attributes and qualities found in nature. This can be hard to measure but is often highly visible since it affects architectural form and appearance.

It should be said that Green too recognises the importance of well-being but the focus here is on physiological well-being through the principle of avoidance. The design team is told, in effect, what not to do¹ in the interest of occupant health and comfort. Biophilic design targets psychological well-being on the grounds that everyone has an innate affinity for nature. The approach here is salutogenic affordance: what to do to improve well-being.

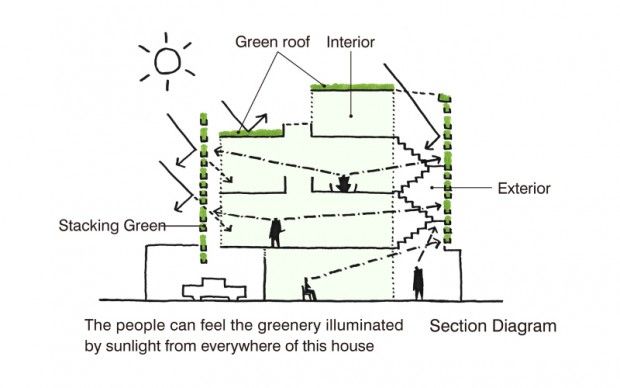

Stacking Green

Greenery, daylight, air flow and views are important to this reinvented tube-house in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, by architect Vo Trong Nghia. The award-winning project – without Green certification – addresses well being at the building and argues for the same at the urban scale.

Drawing by Vo Trong Nghia

What do building users think matters more?

Some 2000 occupants of 11 office buildings in Singapore – a mix of Green certified and non-certified developments – were surveyed on their perception and expectation². Asked if they thought they were in a Green building, a sizeable number in non-certified buildings , almost 14%, said ‘yes’ suggesting a baseline expectation of Green that is not linked to certification.

Asked what they thought was a Green building, the group as a whole – including those in certified buildings – mentioned plants (21.5% of responses) and daylight (19.6%). Energy and water efficiency, sensors, controls and recycling – the focus of many certification tools – were in the subsequent four spots. Certification itself, as a marker of what is a Green building, was mentioned by only 2.4%, a low figure given that almost a third of all buildings in Singapore are presently certified³.

When the same group was asked to pick features/attributes that reduce stress, six of the top ten turned out to be biophilic: presence of plants (58.5%), views out (57%), access to daylight (44.2%), water features (43.9%), courtyard spaces (35.2%) and sounds of nature (35.2%). Only three correspond with certification requirements: noise control (65.4%), air quality (61.3%) and temperature controls (51.2%).

Stacking Green

Vo Trong Nghia - Green façade

Image by Hiroyuki Oki

User response is unequivocally biophilic. But how much corresponding emphasis is there in certification tools?

Fourteen Asian Green certification tools were reviewed4. All tools seem to say greenery and water are important but almost none link these to the question occupant well-being. Of the two, greenery is sometimes parked under ‘Ecology’ where it is tied to natural systems (for instance, the need to preserve existing habitats within project site). Enhancement of green cover is mentioned by some but this is often linked with goals like ‘reduced urban heat island effect.’ The potential of water – salutogenic or ecological – is ignored. The tools are interested in conserving water, and little else.

The review then looked at biophilic attributes: access to daylight and natural ventilation, view to outdoors. The most valued of these are daylight (9 out of 14 tools ask for this) and natural ventilation (8 out of 14). The clauses here often carry a caveat on comfort, worded as the avoidance of visual or thermal discomfort. Tellingly, the clause itself can be parked under ‘Energy’, not ‘Indoor Environmental Quality’. The least valued is view to outdoors; 10 out of 14 tools do not mention this or ask for it in only for some building types.

Stacking Green

Vo Trong Nghia - Daylit Interior

Image by Hiroyuki Oki

The most biophilic tool in Asia is Lotus (Vietnam) in which some 18% of achievable credits are linked to natural systems or biophilic features5. The least biophilic tools, accounting for about 5% or less of possible score, are GRIHA (India), LEED India (India), TREES (Thailand) and GreenSL (Sri Lanka)6.

On the whole, it appears, Asian tools are not deeply biophilic. Biophilic principles are undervalued, either missing or (mis)placed in a category other than well-being. And because these tools drive the definition of Green, it follows that the Green building in Asia does not actively seek biophilic design as a pathway to well-being.

This said, there are notable exceptions…

Continued on Tuesday 9th February 2016

Twitter: @nirmal_kishnani

Email: [email protected]

The review of Asian certification tools was carried out in collaboration with Shuchi Jhalani, a post-graduate student at the School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore.

Published on HUman Space: Consult the source

Additional Reading

¹These are typically parked under ‘Indoor Environmental Quality’ in which outer limits of acceptability are stipulated (for instance, the upper and lower limits of indoor air temperature). The project is penalized if it exceeds these limits.

²The 2012 study was carried out by Kishnani, N. (National University of Singapore), Tan, B.K. (National University of Singapore), Bozovic Stamenovic, R. (University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia); Prasad, D. (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) and Faizal, F. (National University of Singapore). It was sponsored by Singapore’s Ministry of National Development through its research fund for the built environment. It was carried out in collaboration with the Building and Construction Authority (Singapore).

³Building Construction Authority, Singapore (2015); Realising Singapore’s Green Building Dream – Towards a Future-Ready Built Environment. Singapore

4Asian Green certification tools

1. Green Mark (Singapore): RB version 4.1 + NRB version 4.1

2. GBI (Malaysia): RNC version 1.02 + NRNC version 1.02

3. Greenship (Indonesia): All buildings, version 1.1

4. BERDE (Philippines): VRD version 1.1.0 (2013) + CB version 1.1.0 (2013)

5. Lotus (Vietnam): R version 2.0 + NR version 2.0

6. BEAM Plus (Hong Kong): All buildings, version 1.1 (2010.04)

7. CGBL(China): Residential version 2006 + Commercial, version 2006

8. EEWH (Taiwan): EEWH-RS version 2007 + EEWH-BS version 2007

9. TREES (Thailand): All buildings, version 1.1

10. CASBEE (Japan): All buildings, 2011 Edition

11. KGBC (South Korea): Multi-unit residential version 2002 + Others version 2002

12. GREENSL (Sri Lanka): All buildings, December 2010

13. GRIHA (India): SVA GRIHA, version 2013 + All buildings, version 3

14. LEED (India): All buildings, version 2011

5The review looked at clauses for achievable credits only. Most tools also have pre-requisites clauses for which no credits are awarded.

6To put this in perspective, the WELL Building Standard – a new certification tool dedicated solely to occupant well-being – assigns 33% of achievable credits to natural systems and biophilic features.