Part 2: Are Green Buildings Biophilic? Why the answer matters, particularly in Asia

Article by Nirmal Kishnani - Vice Dean at School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore

Continued from Part 1: Are Green Buildings Biophilic? Why the answer matters, particularly in Asia

On the whole, it appears, Asian tools are not deeply biophilic. Biophilic principles are undervalued, either missing or (mis)placed in a category other than well-being. And because these tools drive the definition of Green, it follows that the Green building in Asia does not actively seek biophilic design as a pathway to well-being.

This said, there are notable exceptions. Green Mark version 5 (non-residential), currently in pilot stage, has changed the vocabulary of certification. In a clause on greenery, the team is called on to “integrate a verdant landscape and waterscape that is accessible for all to enjoy… to enhance the biodiversity around the development and provide visual relief to building occupants and neighbours.” In another clause on ‘Well-Being’, biophilic design is explicitly discussed as provision of “elements of nature… to nurture the human-nature relationship… for the health and happiness of the building users.” Version 5, compared with the current version, almost doubles the emphasis on natural systems and biophilic features, accounting for over 20% of possible score, making Green Mark the most biophilic tool in Asia. It will be interesting to see how version 5 changes the look and feel of future Green buildings in Singapore. Other tools, like GRIHA, in newer versions, are also increasing the weightage placed on this although they still lag behind in the final tally.

Jakarta, Indonesia

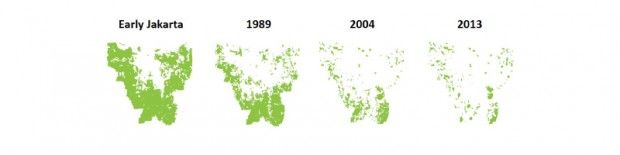

Depletion of urban green cover. Drawing by class of MSc ISD progamme, National University of Singapore, based on Nasa Earth Observatory

Exceptions aside, the general lack of interest in biophilic design is a missed opportunity in Asia because well-being – in many cities – is compromised for the majority of residents. Many cities have been systematically stripped of blue-green cover; once accessible green spaces and waterways are replaced by grey infrastructure and gated communities.

Case in point: the city of Jakarta (Indonesia), since its early days as a metropolis, has seen a loss of green space – from 24% to 9.9% of city area – with a parallel loss of its water footprint from 4% to 2.5%. Green space available to the poor is now estimated at 0.19 m2/person; the affluent have 6.53¹. In the same period, urban density rose from 10,075 to 13,157 people/ km2, with peak density now close to 50,000².

Jakarta, Indonesia

Degradation of waterways due to industrial pollution and dumping

Image by Giovanni Cossu

In a recent study³ it was reported that this transformation has impacted the quality of life in Jakarta. Jakarta was once a water city. Rooted in culture and religion, water was positively perceived. Developments in recent decades have altered this, creating new anxieties and phobias for water. Factories, buildings and roads have turned rivers in narrow concrete, polluted canals; access to rivers and green spaces has been curtailed. This, in turn, has triggered a change in habits; a new generation of Jakartans pollute rivers with garbage and sewage. Waterways have lost their social value, becoming an open dump.

In cities like Jakarta there are no real alternatives to better policy and planning. But until that happens, buildings can do much to compensate. Biophilic design ought to be the centrepiece of design guidelines in Indonesia. Greenship, Indonesia’s Green certification tool, however, offers 7% of available credits to this.

Jakarta, Indonesia

Degradation of waterways due to industrial pollution and dumping

Image by Giovanni Cossu

With tools, there is another problem. Elements and strategies that affect well-being are often parked under something other than well-being. This mis-framing matters. Greenery to reduce urban heat island is good but it carries no obligation for occupant access or enjoyment. As a result, many green roofs are unseen or unreachable.

The Singapore survey of office buildings suggests that Green, at least in the mind of users, is biophilic. It stands to reason that making Green tools adopt biophilic design principles could increase public interest in certified projects. Developers complain that they’d like to go Green but there is too little consumer buy-in. Well, there is now a way to change that.

Twitter: @nirmal_kishnani

Email: [email protected]

The review of Asian certification tools was carried out in collaboration with Shuchi Jhalani, a post-graduate student at the School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore.

Additional Reading

¹“Beban Berat Jakarta” on 20 December 2013

³N. Kishnani and G. Cossu (2015), Enhancing Blue-Green and Social Performance in Dense Urban Environments: Biophilic Design, Singapore’s Khoo Teck Puat Hospital and Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park. National University of Singapore. Sponsored by the Ramboll Foundation